Bridging the data divide in urban planning

Digest #82

Cities are humanity’s hubs of transformation, driving advancements in politics, culture, and the economy. These urban centers enable residents to collaborate on initiatives that enhance community well-being, open pathways for economic mobility, and provide access to essential resources and services. Yet, the surge in urban populations across the globe presents challenges for city planners and policymakers, particularly in managing resources such as housing, water, and food. Data has become a pivotal tool for understanding and meeting residents’ needs. Harnessing data allows authorities to make smarter decisions, and allocate resources in ways that are both efficient and equitable, ensuring the sustainability of urban life.

Effective urban planning relies on precise, inclusive, and up-to-date data. However, many countries face challenges in collecting and utilizing such data due to under-resourced public institutions, limited expertise, and the lack of robust data systems. Comprehensive data involves integrating tools like geographic information systems (GIS), remote sensing, detailed surveys, and participatory community engagement. On the other hand, poor practices such as using outdated records or conducting geographically limited surveys can lead to flawed analyses and ineffective urban policies. Inadequate data compromises planning, resulting in misallocated resources and neglected communities. Public and private organizations must address the challenges that prevent effective data sharing, and ensure that pertinent data is open and accessible to decision-makers.

The challenges and tensions surrounding data sharing

Sharing data that already exists should be a focus for urban planning, and maximizing the huge quantity of data produced by the private sector for public good. Yet, there is an absence of effective data-sharing between public and private organizations. This challenge is often exacerbated by stringent data protection regulations that inadvertently obstruct the exchange of information necessary for public research and crisis management. For example, urban areas collect extensive data on traffic patterns, air quality, and public health, yet these datasets are frequently confined to isolated government departments or municipal authorities. The lack of cohesive frameworks for data-sharing prevents urban planners from obtaining the insights needed to address critical challenges. In the United States, for instance, inconsistencies in state-level data privacy laws pose a barrier to national-level urban development.

In recent years, data-sharing has become deeply politicized, as governments and private entities have begun to impose restrictions to protect proprietary interests, bolster national security, or pursue political objectives. For example, in 2017, Sidewalk Labs, a subsidiary of Alphabet (Google’s parent company), teamed up with Waterfront Toronto to create an ambitious “smart neighborhood” known as Quayside. The project aimed to revolutionize urban living by using advanced data collection to enhance energy efficiency, transportation systems, and public spaces.

However, public concerns quickly arose over how the data collected from residents would be managed. Critics argued the proposal handed significant control over urban data to a private company, raising fears this data would become inaccessible to the public sector. Sidewalk Labs suggested they, rather than the city, should oversee the management of this information, fueling apprehensions that key urban insights would be monopolized for corporate interests. By 2020, mounting public resistance to this data governance model, along with the broader debate over public versus corporate control, contributed to the project's cancellation. Without better and more inclusive data sharing arrangements that facilitate cooperation while reconciling data privacy, the city has lost an opportunity to improve its urban landscape.

This is not an isolated issue; having worked on multiple research projects in urban studies, I have seen firsthand how the lack of accessible data hinders effective development. In my home, the Philippines, the government has launched a number of initiatives to increase public participation in urban planning. One such effort is the Open Data Philippines or ODP, which was launched in 2013 to provide Filipinos with access to datasets from various policy clusters - broad groupings of national government programs that were organized to address specific thematic concerns such as education, healthcare, infrastructure, and economic development to name a few. These clusters were set up to better streamline decision making and promote inter-agency collaboration within these areas, with the overarching goal of improving service delivery.

Then, in 2016, the Freedom of Information (FOI) portal was launched to allow users to request information directly from participating government agencies in the executive branch, such as the Department of Human Settlements and Urban Development (DHSUD) and the Metropolitan Manila Development Authority (MMDA). At the time of writing however, there are no housing and urban development-related datasets available in the Open Data Philippines portal.

The FOI portals of DHSUD and MMDA revealed notable differences in their rates of unsuccessful request processing in 2024. DHSUD reported a low unsuccessful request rate of just 1.6 percent, indicating that only a small number of requests were either denied or left unaddressed. Meanwhile, MMDA’s portal showed a rate of 32.2 percent. This suggests potential challenges within MMDA's FOI framework, possibly due to administrative hurdles or resource constraints. At the local level, we also see issues with effective data sharing; out of the 33 highly urbanized cities in the Philippines, only 14 have posted their land use plans. This makes it harder to work with up-to-date information. Whatever the reason, the public is being denied access to data that could be used for better urban planning and ultimately public good.

The importance of open data in effective urban planning

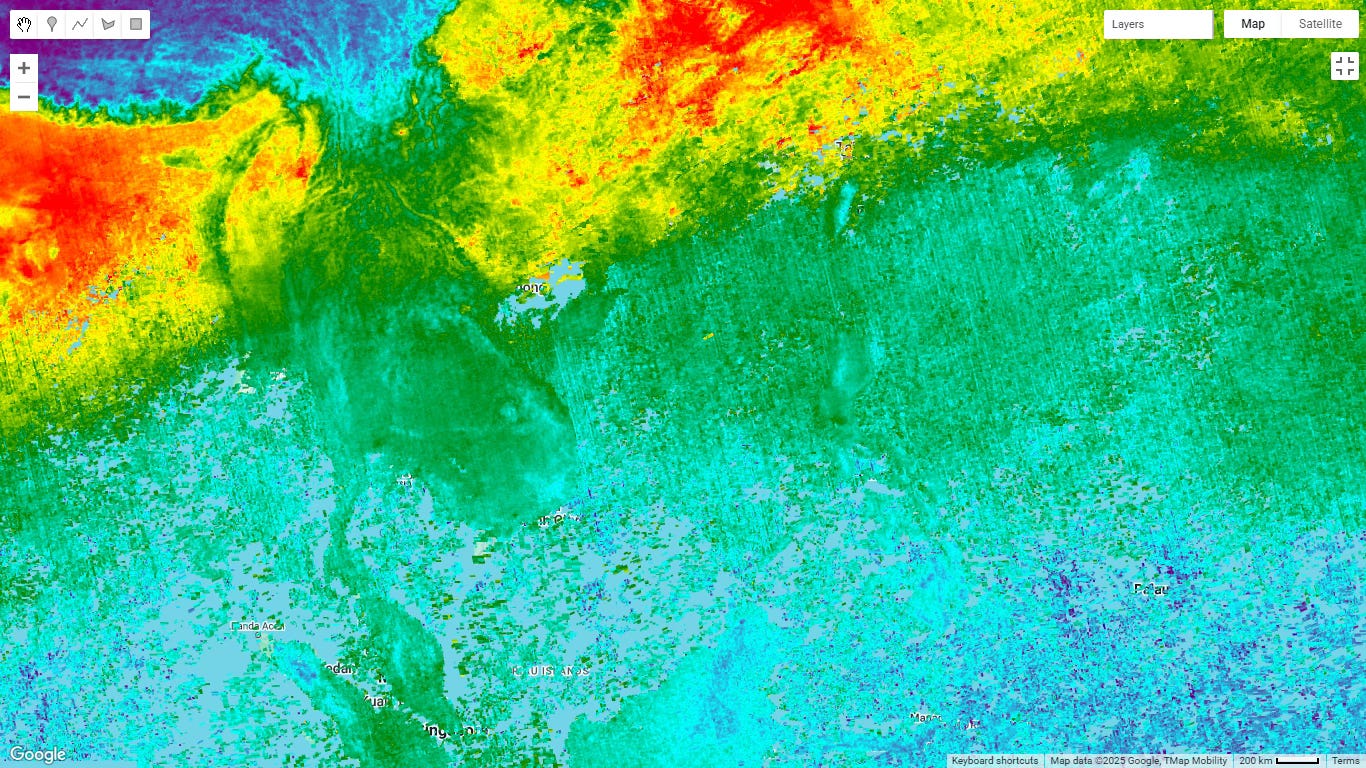

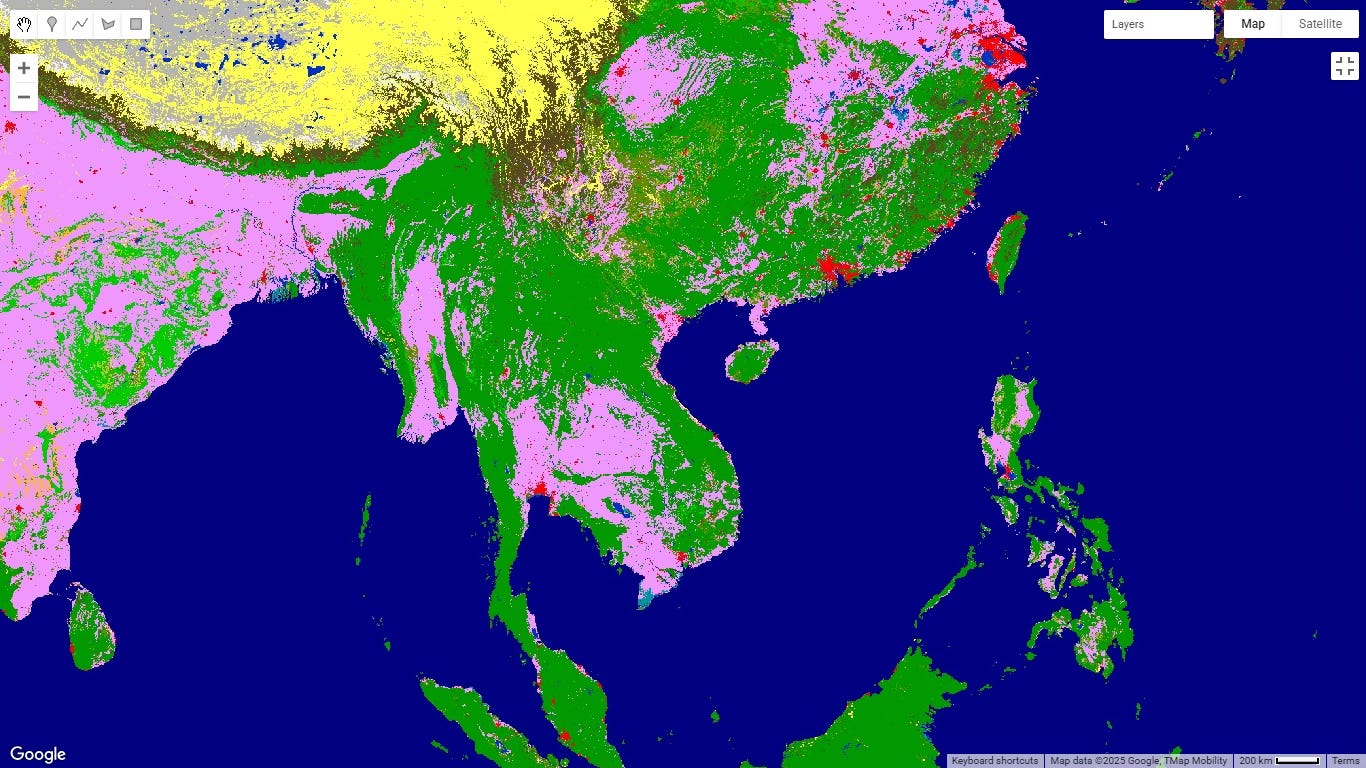

The Philippines case highlights the need to streamline data-sharing policies, especially in the Global South. Bridging these gaps is vital for informed policymaking and development. Governments must adopt proactive, inclusive strategies that bring together diverse stakeholders, including civil society, private sector, communities, and international partners. A key step is investing in remote sensing technologies, which offer data on the layout and physical characteristics of an area from a distance using sensors and other instruments, and making them more widely accessible. Targeted capacity-building is also essential to closing the digital divide and equipping urban planners with the skills to interpret remote sensing data for public good. As well as training government staff, we must also see intergovernmental collaboration and sharing of best practices in data governance. Standardizing data protocols and establishing frameworks for cross-border data sharing can significantly enhance the accuracy, quality, and utility of urban data, fostering a more effective approach to addressing complex city challenges.

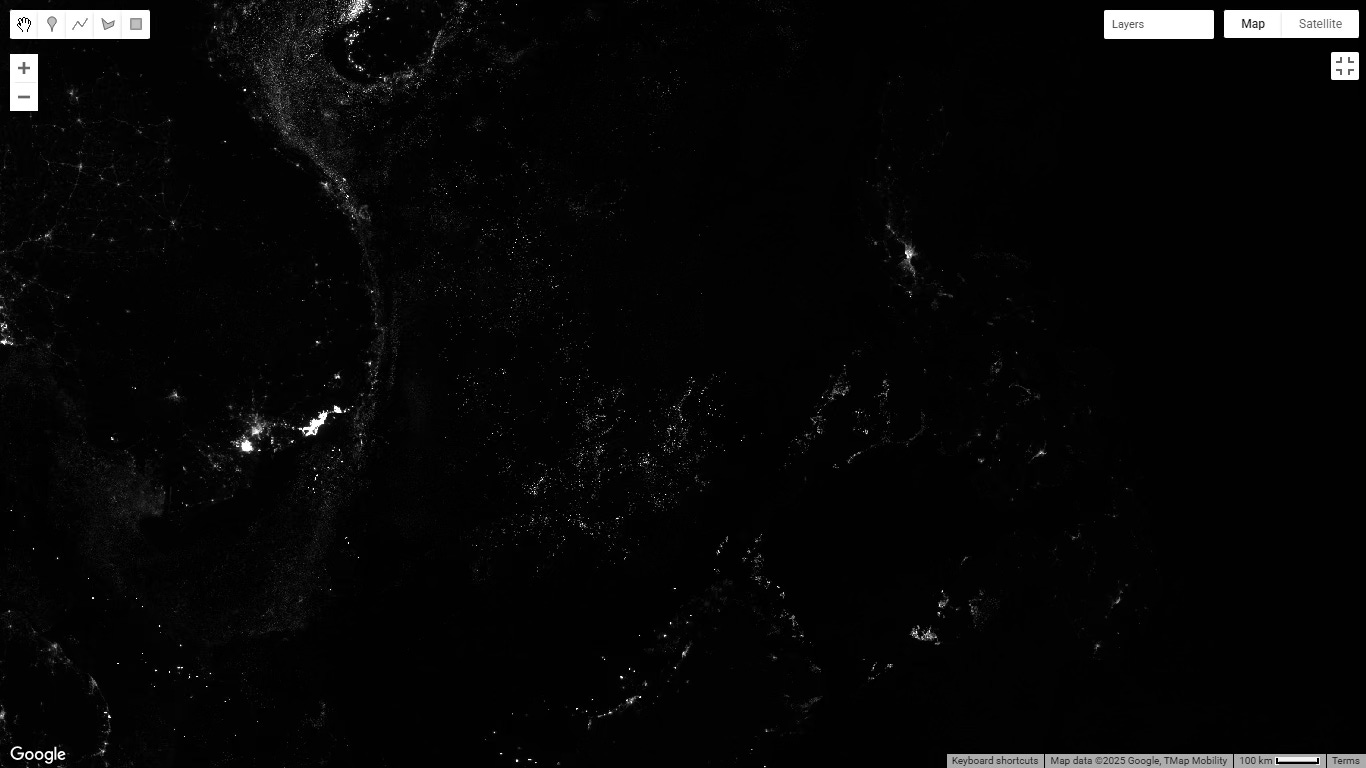

Some private entities have started making their data more accessible to the public, which could serve as a framework for others. For example, Google Earth Engine (GEE) hosts extensive remote-sensing data, offering insights into urban and rural environments across various locations and time periods. The platform includes datasets such as nighttime lights, urban sprawl, and building density, which are invaluable for monitoring urban growth patterns. In addition, international organizations like UN Habitat and the World Bank have developed open data-sharing platforms for the Sustainable Development Goals, which provide access to critical datasets for informed decision-making about urban development.

For example, Dublin City Council launched the Smart Dublin program to help the Irish capital understand environmental conditions and take meaningful steps to improve climate resilience. Using a specially-designed street view car, the program aims to measure key pollutants in the air, which pose risks to both the environment and human health.

Based on the most recent Trendhunters report released in November 2024, the use of remote sensing-assisted drones has been found to deliver critical medical supplies (e.g., blood, organs) faster than traditional methods. This has been piloted in regions like Balbriggan, with potential extensions to areas like the Aran Islands. Remote sensing technologies also contribute to the development of telehealth services in the region by providing real-time environmental and atmospheric data, which improves the precision of diagnoses in rural and remote areas.

How data can fuel equitable cities

While these initiatives provide a framework for public-private sharing for urban planning, they alone cannot eliminate the persistent data divide that limits societal progress. Governments need to share their own data, as well as committing to using privately held data. Additionally, governments must prioritize digital accessibility by expanding broadband infrastructure, providing subsidized devices to low-income families, and embedding digital literacy into school curriculums to train the next generation of data-savvy urban planners. Access to data, and the ability to use it, is essential to unlock data’s potential as a tool for collective good. Cities are our global centers of commerce and culture. Urban resilience is crucial for the success of humankind. Let us prioritize data availability and inclusivity, making it a cornerstone for equitable cities both now and in the future.